The Suicide Risk Care Pathway in Solo Private Practice

In a clinic, suicide risk can become a team problem. Someone can grab a supervisor. Someone can walk the client to a higher level of care. Someone can coordinate follow-up calls. Someone can document while you keep the relationship steady.

In solo private practice, it is different. It is you and the client, sitting across from each other, and your decisions carry extra weight because you do not have a hallway full of colleagues. That reality can make risk conversations feel heavier than they need to be. It can also make some clinicians avoid structure because they worry it will turn the room cold.

A pathway is what keeps it warm.

It lets you stay present and human because you are not inventing the plan in the moment. You already know the next steps. The client can feel that steadiness. You can also feel it.

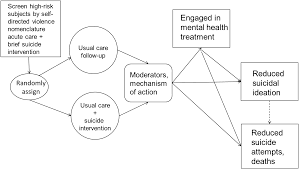

Zero Suicide and similar models describe a pathway that includes identifying risk, engaging the person, treating the drivers, and staying connected during transitions. The Action Alliance’s recommended standard care also reads like a pathway. It includes same-day assessment when a screen is positive, collaborative safety planning, lethal means counseling, and follow-up contact.

The difference in private practice is not the steps. The difference is how you do them without a system around you.

Step 1: Build the pathway before you need it

This is the part most solo clinicians skip because it feels “administrative.” Then the first high-risk moment hits and you find yourself scrambling.

Before you ever need it, you want three things ready.

First, you want a written crisis policy in your informed consent and intake paperwork. Not a dramatic one. Just plain language that says how clients should get help after hours, what counts as an emergency, and what you do if you believe they are at imminent risk.

Second, you want your local resources on one page. The nearest emergency departments. The local mobile crisis team if your county has one. The local crisis line. The non-emergency police number. The addresses. Not “Google it later,” because later is always the worst time. You do not have to advertise that list to clients, but you want it ready.

Third, you want your own boundaries clarified in your head. Can you do brief check-ins between sessions. Do you only communicate by email. Do you have a secure messaging system. What is your response time. If you do not clarify it now, you will end up clarifying it in the middle of a crisis, and that rarely goes well for either of you.

The reason this matters is simple. A client in crisis needs certainty, not ambiguity. A clinician in crisis mode also needs certainty, not improvisation.

Step 2: Identify risk early and consistently

In solo practice, clients are often high-functioning enough to look “fine” until they are not. They may show up on time, speak calmly, and still be seriously struggling.

So you want two ways of catching risk.

One is clinical observation over time. Sudden increase in hopelessness. A sharp drop in sleep. Increased substance use. Missed appointments that are out of character. Big shame after a conflict. A new stressor that collapses their coping.

The other is routine screening in the moments where it makes sense. Many practices use PHQ-9, and item 9 can flag thoughts of death or self-harm that need follow-up. A positive response needs further assessment by someone trained to do it.

Screening is not the clinical work. It is the reason you begin the clinical work.

Step 3: Assess risk in a way that protects honesty

Here is the part that matters most in private practice. If clients think honesty automatically leads to losing control, they will stop being honest.

So your first job is to keep the room safe enough for the truth.

You can say:

“I am glad you told me. I want to ask a few direct questions so I understand what is happening and so we can decide what you need right now.”

Then you ask direct questions about ideation, intent, plan, and behavior, because that is what evidence-based assessment requires when a screen is positive. The Joint Commission describes this as directly asking about ideation, plan, intent, behaviors, and also reviewing risk and protective factors.

If you want structure without sounding robotic, SAFE-T is helpful. It walks you through risk factors, protective factors, suicide inquiry, risk level with interventions, and documentation.

In plain language, you are answering four questions:

Are they thinking about suicide.

Do they want to act on it.

Do they have a plan.

Have they done anything recently that moves them closer to acting.

In solo practice, also add a “real life” layer. Are they alone tonight. Are they intoxicated. Do they have access to lethal means. Are they in a situation where a fight, a breakup, or a humiliation spiral is likely to happen again in the next 24 hours. These are not theoretical questions. They are the difference between outpatient safety and “this needs a higher level of care.”

Step 4: Make a same-day decision about level of care

This is the step that makes solo clinicians sweat because it can feel like there is no perfect option.

A useful way to think is not “How risky are they in general.” A useful way to think is “What happens when they walk out of my office.”

Outpatient care is more likely to be appropriate when there is no current intent, no plan, no recent suicidal behavior, and you can make a realistic safety plan with follow-up that the client can actually do.

Escalation becomes more likely when there is intent, a plan, recent behavior, inability to collaborate on immediate safety steps, severe intoxication, psychosis, or a situation where you cannot build a plan that will hold once they leave.

When you are solo, consultation is one of your best tools. A quick consult does not mean you are unsure. It means you are practicing responsibly in a high-stakes moment. Document the consult and what it informed.

Step 5: Engage through collaboration, not control

If you have to escalate to emergency care, the goal is still collaboration whenever possible. You can explain what you are seeing, what you are worried about, and why a higher level of care is the safest step today.

If outpatient is appropriate, this is where your pathway turns from assessment into action, and the client should feel the shift. They should leave with something concrete.

The Action Alliance recommended standard care emphasizes collaborative safety planning during the same visit for people with suicide risk, plus crisis resources and steps that reduce access to lethal means.

You can frame it like this:

“We are going to build a plan for the next hard moment. Not a promise. A plan. Something you can use when your brain is not being kind to you.”

That language lands better than “contracting.” It feels like care.

Step 6: Write the safety plan as the bridge between sessions

In solo private practice, the safety plan has an extra job. It acts as the “system” that you do not have.

A good safety plan form is short and personal. It is written in the client’s language. It includes early warning signs, internal coping strategies, social supports, professional resources, crisis steps, and a means safety plan. The Safety Planning Guide describes it as a prioritized written list of coping strategies and sources of support that someone can use when risk rises.

Here is the practical way to make it real.

You do it live in session. You do not hand it as homework. You ask for details that are actually usable. You also make them store it somewhere they will find it. Notes app. A pinned note. A screenshot. A printed copy on the fridge if that fits their life.

In solo practice, I would also add one extra line to the plan that clinics often forget. It is the “if I cannot reach my therapist” line. It should spell out the next step clearly, including 988, local crisis options, and emergency services when needed. The 988 Lifeline is designed for call, text, and chat, and many clients will use it more easily if you explain what it is before they need it.

This is also a natural place to use a safety plan template. Not because the template fixes risk, but because it helps you capture the plan cleanly and gives the client something readable when they are overwhelmed.

Step 7: Do lethal means safety in a way that clients can tolerate

This step saves lives and still gets avoided because it can feel awkward.

In solo practice, it helps to frame it as a short-term safety step, not a moral conversation.

“When someone is feeling this low, access matters. I want us to think about making your environment safer for the next few days. What is in your space that worries you, and what is one change that feels doable.”

The Action Alliance standard care includes counseling on reducing access to lethal means as part of the care pathway.

Do not aim for perfect. Aim for real. Locking up medications. Moving extra meds out of reach. Giving a trusted person temporary control. Increasing friction. Making an impulsive moment harder to act on.

Step 8: Follow up in a way that fits solo practice boundaries

This is where solo clinicians often feel stuck. You cannot become a 24/7 crisis line. You also cannot pretend that the week between sessions does not exist.

So you design follow-up that is both clinically meaningful and boundaried.

For some therapists, that looks like scheduling a sooner session or adding a short check-in call. For others it looks like a planned message inside a secure system. For others it looks like coordinated care with a prescriber or primary care provider when the client has consented. What matters is that the plan is explicit, not implied.

Zero Suicide highlights transitions and ongoing connection as part of suicide safer care. The idea is simple. The most dangerous time is often when people feel alone after disclosure. Even a small, planned touchpoint can reduce that feeling.

If you do not offer between-session contact, you can still build “connection” through the plan itself. You can make sure the client has real supports listed, and that they have practiced what they will do if risk rises, and that they have saved crisis resources in their phone.

Step 9: Document the thinking, because the thinking is the care

In solo practice, your note is also your safety net. Not in a paranoid way. In a clinical clarity way.

When standards talk about suicide prevention, they emphasize evidence-based assessment, documentation of risk, and a documented plan to reduce risk

A strong note in solo practice usually reads like this:

Why you assessed risk today.

What the client said and how you clarified it.

What you assessed about ideation, intent, plan, and behavior.

What risk factors and protective factors were present.

What actions you took in session, including collaborative safety planning.

What you discussed about reducing access to lethal means.

What the follow-up plan is, and what crisis steps were reviewed.

Whether you consulted anyone, and what that consultation informed.

That note tells the story of care, not just the story of documentation. Using a structured clinical documentation template can help ensure all these critical elements are captured consistently, saving time and reducing administrative burden. Many solo practitioners find such templates through resources like WordLayouts.

Step 10: Keep the pathway alive, because risk changes

In solo practice, the pathway becomes a rhythm. You do not use it once and forget it.

SAFE-T emphasizes reassessment when ideation increases, when clinical status changes, or when there are new stressors.

So you revisit the plan like it is a living document. You ask what parts were used, what parts were unrealistic, and what needs to change. You also pay attention to the client’s patterns over time, because the pattern is often more informative than the single moment.

The quiet goal of the whole pathway

The real goal of a suicide risk care pathway in solo private practice is not to become perfect at crisis management. It is to become reliably calm and reliably helpful.

When you have a pathway, you do not need to perform confidence. You can actually feel it. The client senses it. That alone can lower risk, because panic and uncertainty are contagious.

And when the client leaves your office after a hard conversation, the pathway means they leave holding something real. They leave with a plan they helped build, supports they can reach, and a clear next step if the night gets ugly.

That is not paperwork. That is outpatient care at its most important.